UK Racings Alphabet Soup Gridlock and its not Just 5Cs

12 acronyms. Zero authority. One outcome: decline. British racing doesn't have a leadership problem. It has a structure problem.

HORSE RACINGGENERALBUSINESS

Ed Grimshaw

12/18/20257 min read

British horseracing stands at a crossroads that increasingly resembles a cliff edge. The sport that invented the thoroughbred, established the template for racing worldwide, and once commanded unquestioned global supremacy now confronts an uncomfortable reality: its very structure may be engineering its demise. The question is no longer whether reform is necessary, but whether the industry possesses the collective will to implement it before the mathematics of decline become irreversible.

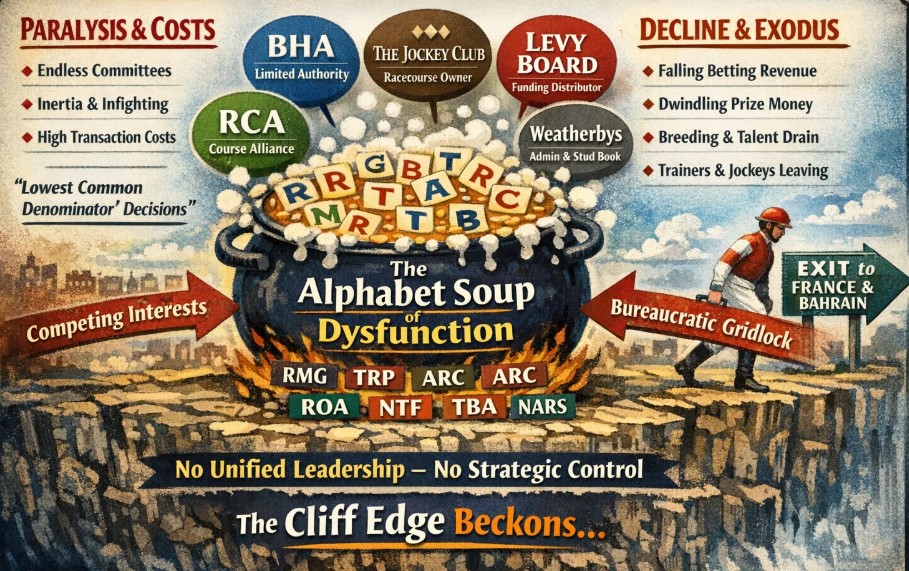

The Alphabet Soup of Dysfunction

Attempt to understand British racing's governance and you quickly encounter a bewildering proliferation of bodies, each with overlapping remits, competing interests, and their own bureaucratic imperatives. The BHA. The Jockey Club. The RCA. Weatherbys. The Levy Board. Great British Racing. Racing Enterprises Limited. The Thoroughbred Group. The ROA, NTF, TBA, PJA, NARS. RMG. TRP. ARC. The Racing Foundation. British Champions Series. Britbet. Each acronym represents offices, boards, committees, executives, and—inevitably—costs.

Consider the architecture. The BHA is nominally the governing body, yet its authority over commercial matters is severely constrained. The Jockey Club, founded in 1750, no longer regulates but owns 15 racecourses, controls 50% of RMG, holds 37% of British Champions Series, and maintains 34% voting rights in Britbet—making it simultaneously a stakeholder, competitor, and influencer without formal governance responsibility. Weatherbys administers racing under BHA contract, maintaining the General Stud Book, processing entries and declarations, and providing financial services. The Levy Board, a non-departmental government body under DCMS, collects and distributes betting levies but operates independently of BHA strategic direction.

Then comes the promotional apparatus. Great British Racing is the official marketing body, operating as the arm of Racing Enterprises Limited, itself a 50/50 joint venture between the RCA and the Thoroughbred Group. The Thoroughbred Group comprises the ROA (representing 8,000 owners), the NTF (trainers), the TBA (breeders), the PJA (jockeys), and NARS (stable staff). Each maintains its own organisation, staff, and advocacy agenda. The RCA represents 59 racecourses but cannot compel unified commercial action from members who simultaneously compete with each other for fixtures, media rights, and attendance.

Layer upon this the Commercial Committee, the Fixtures and Funding Group, the Racing Group, the Gambling Strategy Group, the Flat Pattern Committee, the Jump Pattern Committee, the Medical Advisory Committee, the Racecourse Committee, the Ethics Committee, and sundry working parties. Each meeting consumes executive time. Each body requires servicing. Each decision requires consultation across multiple stakeholders whose interests frequently diverge.

The Cost of Coordination

This institutional complexity is not cost-free. Every body requires governance, administration, and executive leadership. Every interface between organisations creates transaction costs—time spent in meetings, energy expended on coordination, delays while consultation processes grind through. The opportunity cost of having talented individuals navigate Byzantine committee structures rather than driving change is incalculable but certainly substantial.

More damaging still is the structural incentive toward inertia. When any significant decision requires consensus across bodies with divergent interests, the path of least resistance is always the status quo. The RCA cannot bind its members to unified commercial positions. The Thoroughbred Group must balance the sometimes-conflicting interests of owners, trainers, breeders, jockeys, and staff. The BHA can recommend but rarely compel. The result, as Lord Allen recently acknowledged, is "lowest common denominator decision-making."

Compare this to France Galop, which governs French racing with integrated authority over 115 racecourses. Or Hong Kong's Jockey Club, which operates as a unified entity controlling racing, betting, and prize money distribution. These jurisdictions can make strategic decisions and implement them. British racing can, at best, broker compromises that leave underlying structural problems unaddressed.

The Independent Board Illusion

Lord Allen's stated ambition to populate the BHA board with independent members untied to particular sectors sounds progressive. "Change needs to happen at the top," he declared at the Gimcrack Dinner. But what, precisely, will an independent BHA board actually control?

Not media rights—those belong to racecourses through RMG and TRP. Not the levy—that's the HBLB's domain. Not racecourse operations—the RCA members run those independently. Not the fixture list beyond strategic fixtures—the 2004 OFT ruling ensured racecourses control their own programmes. Not promotion—that's Great British Racing through REL. Not ownership recruitment—the ROA handles that. Not training standards—the NTF represents trainers' interests. Not breeding incentives—the TBA advocates for breeders.

The BHA can regulate, license, and enforce rules as it chooses. It can convene stakeholders, facilitate discussion, and publish strategies. It can adjust fixture allocations at the margins and recommend prize money distributions. But it cannot compel commercial consolidation. It cannot force racecourses to sacrifice individual media revenue for collective benefit. It cannot override the rational self-interest of independent actors whose livelihoods depend on maximising their own returns.

An independent board governing an organisation without meaningful power is governance theatre. It may produce better-quality analysis and more coherent strategic documents. It will not solve the fundamental problem: that no entity in British racing possesses the authority to implement transformational change against the wishes of entrenched interests.

The Media Rights Fragmentation

The media rights landscape exemplifies this dysfunction. Racecourse Media Group represents 37 courses through a cooperative model, generating £113 million for shareholders in 2024. Arena Racing Company owns 16 tracks and operates through The Racing Partnership. Independents like Ascot, Chester, and Newbury negotiate separately. Each group guards commercial interests zealously—Newbury's recent switch to TRP, promising a 13% prize-money increase, represents rational individual behaviour that fragments the overall product further.

The consequences cascade. Punters need multiple subscriptions to watch all British racing. Bookmakers negotiate separately with different rights holders. International distribution lacks the coherence of a unified product. And each course's incentive remains maximising its own media revenue rather than optimising the collective appeal of British racing as a betting and viewing product.

As Charlie Munger observed: "Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome." Racing's incentives reward the next meeting, not the next decade. This short-termism runs so deep that it has become structural rather than behavioural.

The Vicious Spiral

The numbers tell a story of accelerating decline. Online betting turnover fell to £9.12 billion in 2022-23—a £900 million year-on-year decline that, adjusted for inflation, represents a £1.75 billion real-terms contraction. Q1 2025 data shows this trajectory steepening: betting turnover dropped 9% compared with the previous year, with average turnover per core fixture falling 14.4%. The IFHA data is equally sobering: turnover fell from £13.4 billion in 2019-20 to £11.8 billion in 2023-24, erasing fifteen years of growth.

The breeding industry exhibits what economists call negative elasticity of supply. As costs rise and returns diminish, production capacity is permanently withdrawn rather than temporarily reduced. Only three new stallions retired to British studs for the 2025 season; total stallions have fallen from 147 in 2021 to 107 currently. Trainers are relocating to France and Bahrain. Jockeys are seeking opportunities overseas. The horse population on 31 March 2025 stood at 15,070, down 1.9% year-on-year.

Smaller fields weaken the product; a weaker product depresses betting turnover; falling turnover squeezes media rights and prize money; reduced prize money accelerates industry exit. This is not a cycle that will self-correct. It is a spiral whose endpoint is contraction until some reduced equilibrium is reached—or until the industry becomes commercially unviable at anything approaching its current scale.

The French Comparison

France Galop demonstrates what integrated control can achieve. The PMU betting monopoly channels revenues directly back into the sport, funding prize money that puts British equivalents to shame. The winner of a mid-level French race takes home between €9,000 and €15,000; the British equivalent yields £1,000 to £1,500. French-bred horses receive premiums adding 75% to prize money for two and three-year-olds, actively incentivising domestic breeding. Training fees are lower. Travel is subsidised. Entry fees for non-pattern races don't exist.

The results are measurable. France's foal crop has grown 25.6% since 2002. Britain's has declined 7.9%. Trainers Adam West and Amy Murphy have relocated to France. Dan and Clare Kubler have moved to Bahrain. These are not anomalies; they are rational responses to distorted incentives that Britain's fragmented structure cannot correct.

What Radical Restructure Would Require

Genuine reform would require measures that seem politically impossible within current structures. Consolidation of the alphabet soup into a single governing entity with actual commercial authority. Centralised media rights negotiation, eliminating the RMG/TRP fragmentation. A reformed levy structure that captures offshore and international betting. Strategic fixture reduction that prioritises quality over quantity. Prize money distribution mechanisms that incentivise domestic breeding.

Most fundamentally, it would require racecourses, owners' groups, trainers' federations, and other stakeholders to cede autonomy to a central authority empowered to make decisions in the collective interest—even when those decisions disadvantage particular constituencies. It would require the Jockey Club to relinquish its commercial holdings or subordinate them to unified industry governance. It would require the dissolution of bodies that exist primarily to represent sectional interests in negotiations with other sectional interests.

The likelihood of such reform emerging voluntarily from within the existing structure is effectively zero. Turkeys do not vote for Christmas. Bodies do not vote for their own abolition. Executives do not advocate for the elimination of their roles.

The Question Racing Cannot Answer

Lord Allen's "five Cs"—convene, collaborate, coordinate, commercialise, communicate—represent aspiration rather than strategy. They describe what a functioning industry would do, not how to transform a dysfunctional one. The fundamental question remains unanswered: who has the authority to implement transformational change, and what mechanism exists to overcome the structural vetoes embedded throughout the system?

The historical precedent is not encouraging. Racing has faced existential warnings before and responded with incremental adjustments that preserved existing power structures. The BHB became the BHA. Committees were renamed. Strategies were published. The underlying fragmentation remained untouched because addressing it would require someone to lose power, revenue, or relevance—and the system provides no mechanism for imposing such losses over objections.

The sport that created the Derby, established global breeding standards, and exported racing expertise worldwide now faces the ultimate test: whether it can transcend its own structure to survive. An independent BHA board is not the answer when the BHA lacks the authority to implement answers. More committees are not the solution when committees are the problem. Better coordination between fragmentary bodies cannot substitute for the unified authority that coordination's necessity demonstrates is lacking.

Radical restructure is not one option among many. It is the only path that does not lead, eventually, to irrelevance. The alternative—managed decline punctuated by periodic crises, with 40% of racecourses, studs, and training yards potentially closing within five years—is not stability. It is slow-motion collapse with the illusion of continuity.

The mathematics of decline do not negotiate. They do not attend committee meetings. They do not respect stakeholder consultations. They merely compound, indifferent to the elegance of governance structures that cannot prevent them.