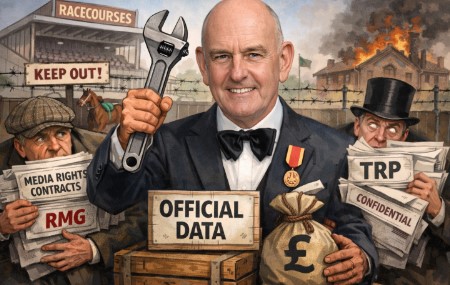

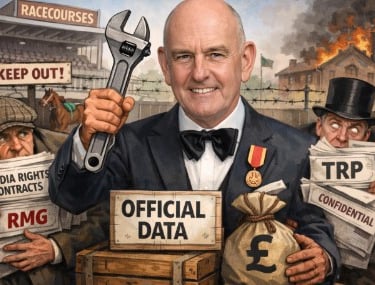

“The Man with the Wrench: How Lord Allen Sparked a Turf War by Actually Doing His Job”

British racing’s power brokers are in uproar after the BHA chair dared to touch their sacred data pie. If reform means sacrificing control, the sport would apparently rather eat itself.

HORSE RACINGBUSINESSSPORT

Ed Grimshaw

1/7/20264 min read

By the seventh day of January, most people are nursing hangovers, lurching towards dry salads and breaking treadmills with feigned sincerity. Not Lord Allen. The newly minted BHA Chair decided to spend the New Year rummaging through media rights contracts like a suspicious Victorian butler rooting through the master’s desk — only to emerge clutching a dusty clause and declaring: “This one’s mine.”

What followed, as reported in Nick Luck Daily, was a masterclass in British sporting politics: bureaucratic, parochial, and simmering with petty vengeance. Allen, brought in to make racing more “commercial,” has done just that — by trying to commercially detach the one piece of the data pie still notionally administered by the BHA: the official result, race distances, photo finishes, and integrity-flavoured clerical crumbs. Not glamorous. Not sexy. But apparently just lucrative enough to spark a civil war.

According to one unnamed wag — and in racing, all the best sources are wags with racing club lanyards and strategic amnesia — Allen has “united the racecourses.” Not in triumph. Not in strategy. But in white-knuckled opposition to a man with the temerity to suggest that the governing body might govern. It’s an achievement not unlike convincing a pride of lions to unionise. And yet, here we are.

The Jockey Club, predictably dressed as the dignified wing of the feudal estate, is playing diplomatic bridge. “We don’t like it,” they mutter with pursed lips, “but we’ll talk.” The smaller tracks, meanwhile, are staging a full-blown constitutional rebellion, presumably led by someone with a pitchfork, a PowerPoint, and a fax machine from 2007.

You’d be forgiven for thinking Lord Allen had suggested euthanising ponies live on Sky Sports. Instead, he merely floated the idea that the BHA might have the right — legally, ethically, commercially — to treat official result data as something more than a free gift to the entrenched media rights brokers.And this, somehow, is heresy.

It’s worth pausing here to admire the absurdity: the BHA currently administers the very building blocks of post-race integrity — official results, distances, photo finishes — but gets about as much commercial respect for it as a steward with a broken radio and a thermos of lentil soup. The racecourses, via RMG and TRP, just scoop it up, bundle it with pictures, and sell it to the bookmakers like a Tesco meal deal: camera, commentary, and a free side of regulation-grade data. Allen, bless him, read the fine print. And in doing so, did something almost unheard of in British racing governance: he acted like a man with a backbone.

He saw a legal seam. He picked at it. And in doing so, revealed the whole grubby weave: a sport too hooked on old habits and closed-shop contracts to even consider a modest rebalancing in favour of participants, or, heaven forbid, integrity. Now let’s be fair. This is the same Lord Allen who arrived in office to the sound of rapturous applause from people like Wilf Walsh — the very same people now describing his behaviour as “mission creep,” which in racing is a polite euphemism for “trying something new and making us uncomfortable.”

Allen was brought in as a fixer. A wheeler, a dealer, a man to bring third-party capital, improve governance, and plug the gaping cash holes left by decades of under-ambition and wild optimism. What he was not, apparently, supposed to do was interfere with the delicate cartel that is British racing’s media rights industry — a beast so sprawling and incestuous it makes the Medici family look like a village pub quiz team.

But interfere he has. And what’s become clear — in the podcast, in the whispers, in the clinking of gin glasses at Newbury — is that Allen is now the first person in years to walk into British racing, actually read the paperwork, and ask why the hell the BHA isn’t charging for the one thing it objectively controls. This is not revolution. This is Accounting 101.

And yet, the whisper mill is already humming: maybe he won’t last. Maybe it’s all too much. Maybe Allen will take his gold watch, his wrench, and his burning deck metaphor, and quietly leave by Cheltenham. He hasn’t got his CEO yet. He hasn’t got his full independent board. And judging by the pace of structural reform, he probably hasn’t got his coat off. The tragedy? If Allen walks, it won’t be because he was wrong. It’ll be because he dared to act in a system that punishes action. The BHA, historically, has had all the authority of a conker on a string. But give it a pair of bolt cutters and a vague idea about revenue redistribution? Suddenly, that’s an existential threat.

And yet, while the governance trench war festers, the sport itself is…fine. Crowds at Christmas were healthy. Warwick was hopping. Musselburgh sparkled. Even Wolverhampton managed a bit of festive cheer. And what do we hear from the great and good? Blank stares. Shrugs. A senior racing official, when confronted with good attendance numbers, reportedly muttered “Quite good” like a hostage reading a ransom note. This is the default posture of too many British racing leaders: apologising for success while preparing the next crisis.

It’s not Lord Allen who lacks vision. It’s the system. A system so averse to change that even success is met with weary suspicion. A system where racecourses clutch media rights contracts like Victorian widows clutching pearls, and where the governing body floats a revenue idea and is met with the kind of panic usually reserved for whip reviews and HRI press releases.

But here’s the twist. Allen might survive. The row might cool. A deal might be done. And if he holds his nerve, he might just nudge British racing into a future where the central regulator has real teeth — not just for enforcing rulebooks but for shaping the sport’s financial reality. He might also just get sick of it all and wander off to a boardroom with fewer barons and better sandwiches.

Either way, he’s done something important: reminded the sport that “governance” is not a dirty word, and that someone — anyone — should be looking after the whole shop, not just the tills. Because if British racing can’t find room for a man with a plan, a wrench, and a medal, then it deserves every inch of the mediocrity it’s been cantering towards for the last two decades.