Jump Racing: The Sport of Kings at Plumpton

Explore the latest in jump racing at Plumpton this week. Delve into the sport of kings and discover why this beloved horse racing event is facing challenges, as the monarch appears to have abdicated.

Ed Grimshaw

11/18/20244 min read

Four Runners and a Funeral (for Excitement)

If jump racing is the sport of kings, then this week’s offerings from Plumpton and its beleaguered companions suggest that the monarch has abdicated. Four-runner fields at Plumpton, Exeter barely assembling enough competitors to count as a race, and Fakenham looking like it’s holding a warm-up for a Christmas donkey derby. Forget betting strategies—at this rate, you can make your pick by flipping a coin.

Tracks like Plumpton, long celebrated for their gritty charm and local heroes, are now ghostly shadows of their former selves. And while the British Horseracing Authority’s (BHA) Richard Wayman has been trotted out to offer some cautious optimism, it’s starting to feel like he’s a jockey saddling up for a lost cause. Reflecting on 2023, Wayman reassures us that “lessons are being learned” and insists that “adjustments will grow the sport’s popularity for years to come.”

Lessons, you say? That’s encouraging. Although based on the current state of jump racing, the main lesson seems to be that empty fields are excellent for traffic-free parking at your local racecourse.

The BHA’s Silence: A Leadership Whoopsie

Let’s be clear—this isn’t all Richard Wayman’s fault. He’s the public face of a sinking ship, while the rest of the BHA board appear to be hiding below deck, presumably debating what kind of hors d'oeuvres they’d like for the lifeboats.

While Wayman waxes lyrical about long-term fixes, the BHA board has said little of substance, leaving grassroots racing to stumble along on its own. Field sizes are shrinking, trainers are grumbling, and owners are fleeing faster than a novice hurdler faced with Cheltenham’s infamous final climb. And now, much of British racing’s best talent has been shipped off to Ireland, leaving our beloved sport in an increasingly precarious position.

But hey, maybe the BHA board is simply too busy “learning lessons” themselves—perhaps about how to stay silent while grassroots jump racing gasps for air.

Irish Domination: Britain’s Talent Drain

Jump racing’s brightest stars are no longer gracing Plumpton or Fakenham with their muddy magnificence. No, they’ve been whisked across the Irish Sea, lured by the siren song of bigger prize pots, robust government support, and a racing scene that hasn’t yet forgotten how to throw a decent competition.

These days, Ireland dominates jump racing like an older sibling hogging the toy box. Willie Mullins, Gordon Elliott, and Henry de Bromhead have turned the Cheltenham Festival into their personal showroom, leaving British trainers scrambling for scraps. Even British-bred horses are now running in Irish colours, as owners realise there’s no point faffing around at Plumpton when Leopardstown is offering a king’s ransom in prize money.

If the BHA doesn’t act soon, Cheltenham might just rebrand itself as The Irish Open.

2023 Jump Racing in Numbers: The Great Divide

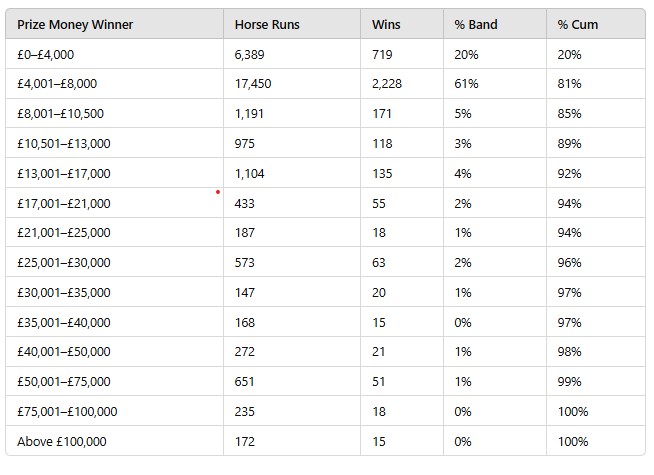

To make matters worse, the 2023 figures tell a story of sharp inequalities in prize money, and with it, stark imbalances in field sizes. Take a look at this table—it’s about as cheerful as Plumpton’s crowd during a midweek downpour:

See Table in Photo above

What jumps out—pun intended—is that most of the action is taking place in the £0–£4,000 prize-money bracket, where over 6,000 runners compete for crumbs. Meanwhile, the elite races with six-figure pots attract fewer than 350 horses. It’s a pyramid scheme, with grassroots jump racing propping up a gilded elite at the top.

And while we can’t expect every race to host a 10-runner cavalry charge—especially in jumps racing, where attrition rates can make Brexit negotiations look efficient—a target of at least seven runners per race seems both reasonable and necessary. At the very least, it’d give punters something to cheer for, rather than spending half the race wondering which unlucky fourth-place finisher will grab the last rosette.

Why the Runners Have Run Away

There’s no single culprit behind the decline in British jump racing, but a trifecta of problems stands out:

Cost of Ownership: Rising costs for feed, transport, and veterinary care have made owning a jump horse a luxury few can justify—especially with poor prize money at the grassroots level.

Fixture Overload: Too many races spread the available horses thinner than butter on a budget airline sandwich, leaving smaller tracks to cobble together lacklustre fields.

Stagnant Prize Money: Prize pots have failed to keep pace with rising costs, forcing owners and trainers to seek greener pastures—or, more often, Irish ones.

Irish Exports: Leaving fewer UK based Horses to run on home soil.

The Solutions: Fix It, Don’t Fudge It

If jump racing is to survive—and thrive—beyond 2026, the following changes are essential:

Redistribute Prize Money: Tracks like Plumpton and Fakenham need meaningful financial support to attract owners and runners. Increasing payouts in the £0–£4,000 bracket would boost field sizes and reinvigorate grassroots jump racing.

Cut the Fixture List: Fewer races would mean bigger, more competitive fields, providing better value for fans, bettors, and owners alike.

Focus on Experience: Jump racing isn’t just about betting slips—it’s about the atmosphere, the drama, and the mud-splattered spectacle. Tracks need to become community events that draw in crowds, even if they’re more interested in the Guinness tent than the paddock.

A Future Worth Betting On?

Wayman’s optimism and the grim realities of British jump racing may seem worlds apart, but they don’t have to be. There is a path forward, but it requires decisive action—not just from Wayman, but from the BHA’s silent board, which must abandon its dithering and take responsibility for the sport’s future.

The truth is stark: without bold reforms, four-runner races could become the norm, and grassroots jump racing may fade into obscurity. Optimism for 2026 means nothing if it isn’t accompanied by immediate, concrete action.

And let’s not ignore Ireland’s role in jump racing’s decline. The export of Britain’s brightest prospects to Irish yards has left a gaping hole in the domestic scene. If the BHA doesn’t act soon, it won’t just be Cheltenham dominated by Irish horses—it’ll be British jump racing reduced to a footnote.

So, BHA, the ball (or horse) is in your court. Will you rise to the challenge, or continue “learning lessons” while jump racing quietly jumps off a cliff?