Did Transparency Ever Exist at The Jockey Club?

The Kempton Park affair isn’t a planning dispute—it’s a live test of whether transparency at The Jockey Club is principle or performance

HORSE RACINGBUSINESSPOLITICSSPORT

Ed Grimshaw

12/19/20256 min read

The Harding Test: Does Transparency Mean Anything?

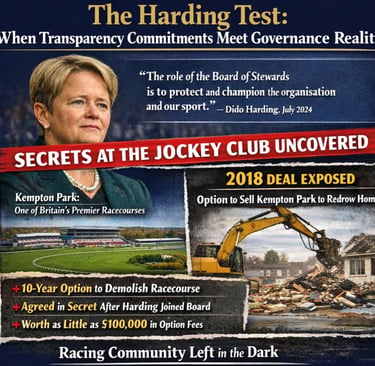

In July 2024, Dido Harding became Senior Steward of The Jockey Club with a promise that now demands reckoning. "The role of the Board of Stewards," she declared, "is to be both support and challenge to The Jockey Club's leadership team, to protect and champion the organisation and our sport and to ensure we all live up to our mission to further the long-term good of racing."

Eighteen months later, those words ring hollow. For seven years, The Jockey Club concealed a secret that strikes at the heart of British racing's governance crisis. In 2018—three months after Harding joined the Board—the organisation granted property developer Redrow Homes a decade-long option to bulldoze Kempton Park. The deal, possibly worth as little as £100,000, handed control of a profitable racecourse to developers without informing a single trainer, owner, or jockey whose livelihood depends on its survival.

Harding sat on the Board throughout this concealment. She now chairs the institution responsible for it whilst proclaiming commitment to transparency. The question is simple: will she demonstrate her values are genuine, or confirm they were always just public relations?

The Concealment She Presided Over?

The timeline is damning. January 2017: The Jockey Club announces closure plans. The backlash is immediate—trainers, owners, jockeys unite in opposition. 2018: After Harding joins the Board, The Jockey Club secretly grants Redrow the option. No consultation with stakeholders. No disclosure to the sport. February 2020: Senior Steward Sandy Dudgeon announces Kempton is "saved" with a scaled-back development—whilst concealing the Redrow option remains fully operational. Harding was present throughout. Seven years of silence followed until investigative journalism exposed the truth in June 2025. CEO Jim Mullen's December admission that Kempton's future is "out of my hands" confirmed what stakeholders already suspected: their supposed guardians had sold them out.

The February 2020 announcement wasn't merely incomplete—it looks strategically constructed to mislead. Silence, when disclosure is owed, is indistinguishable from deception. Whether Harding crafted this message, acquiesced to it, or failed to challenge it is precisely what she must now answer.

The Section 172 Problem

Harding's obligation extends beyond moral leadership to statutory duty. Under the Companies Act 2006, The Jockey Club's Section 172 statement claims it "engages with stakeholders on material decisions." This is provably false. A decade-long development option is unequivocally material. Yet no engagement occurred with the National Trainers Federation, Racehorse Owners Association, Professional Jockeys Association, or even the British Horseracing Authority. As a Steward from 2018, Harding bears responsibility for this failure. As Senior Steward, she bears responsibility for addressing it.

Section 172 requires directors to consider stakeholder interests: employees, suppliers, customers, community impact, reputation, fairness. The Kempton concealment violated every dimension. Trainers scheduled operations, owners made investment decisions, jockeys planned careers—all without knowing Kempton's future was subject to a developer's commercial calculations.

The failure to disclose material information whilst claiming stakeholder engagement doesn't merely breach governance standards—it potentially exposes directors to claims of breach of statutory duty. Whether such claims succeed depends partly on documentation Harding now controls.

What Did Dido Know?

Critical evidence remains concealed—evidence Harding has power to release:

2018 Board minutes: Did she vote to approve the Redrow option? Did she raise concerns about concealment? Did she question the wisdom of keeping stakeholders ignorant?

Internal communications: Was she aware of the decision to maintain silence? Did she challenge it? If she dissented, what actions did she take?

February 2020 documentation: Did she know the announcement was misleading? Did she understand that messaging Kempton as "saved" whilst maintaining an undisclosed option constituted misrepresentation?

Without these documents, we cannot determine Harding's culpability. But this uncertainty itself represents governance failure. Transparency requires not merely avoiding deception but affirmatively disclosing material decisions and the processes that produced them. Here's what we know: Harding joined the Board three months before the option was granted. She remained on the Board throughout seven years of concealment. She now chairs the organisation whilst proclaiming transparency. If she participated in the decision, she must explain why. If she was kept ignorant, she must explain why Board governance permitted such opacity. Either answer is damning.

The Commercial Betrayal

The Jockey Club will claim it acted in racing's interests—but whose definition? Kempton provides the only venue in Britain where top-class jump horses can race on suitable ground at Christmas. Aintree, Sandown, Ascot produce heavy ground when climate change promises warmer, wetter winters. Kempton somehow produces good-to-soft ground when only Musselburgh and Ludlow manage similar—neither suitable for Grade 1 racing. This isn't sentiment—it's commercial reality. Elite horse trainers and owners become less inclined to run at Christmas, more likely to choose Ireland where most good horses already train and deep-pocketed owners increasingly base operations. British trainers struggle with greater overheads and absent subsidies. Closing Kempton accelerates the exodus precisely when British racing's supply chain risks collapse.

High-class horses drive attendances—betting customer increases and retainments are greater during festivals than run of the mill fixtures. Fewer quality horses at Christmas means reduced turnover, lower attendance, contracted media appeal. The Jockey Club says it will invest in Cheltenham and Aintree—as satellites to an Irish system, what purpose would they serve? Yet The Jockey Club published no analysis weighing these systemic risks. If Harding participated in Board discussions dismissing infrastructure concerns as sentiment rather than commercial analysis, she bears responsibility. If such analysis was never conducted, she bears responsibility for that failure of due diligence.

The Transparency Test

Harding established the standard: the Board provides "challenge" to leadership. The Kempton option represents comprehensive failure of that challenge function during her tenure. She now possesses authority to demonstrate whether transparency means anything:

Commission independent review with findings published without redaction.

Apologise publicly for concealment violating chartered obligations.

Release Board papers from 2017-2020: What information was presented? What discussions occurred? What concerns were raised? What decisions were taken?

Implement binding disclosure protocols requiring publication of material commercial decisions within defined timeframes, with sanctions for non-compliance.

Establish mandatory stakeholder consultation before major asset decisions, with documented processes ensuring genuine voice before commitments are made.

Explain her own role: What did she know? When? What did she do? Did she vote to approve? Did she raise concerns? If uninformed, what does that reveal about governance?

Alternatively, she can maintain institutional silence, protect those responsible, and confirm that transparency was always marketing copy. This choice will define whether The Jockey Club's governance model can evolve or whether reform requires external imposition.

Democracy as Last Resort

Kempton's fate ultimately rests with Spelthorne Borough Council's planning system—the democratic forum that aristocratic governance denies. Designated as "strongly performing Green Belt" with "important strategic function," policy presumption runs against development. Here, stakeholders denied voice by closed governance possess statutory rights to be heard. Trainers' federations, owners' associations, racing charities, bookmakers, broadcasters can present evidence of impacts. If planning permission is refused, democracy will have corrected what governance failed to prevent.

This public battle represents direct consequence of governance failure—the final recourse for stakeholders denied consultation by the organisation holding itself out as racing's guardian.

The Binary Choice

Harding made transparency the standard of her leadership. She declared the Board's role to "challenge" decisions and "ensure we all live up to our mission." The Kempton option represents comprehensive failure of that challenge.

Section 172 imposes continuing duty—not merely avoiding future failures but remedying past breaches of stakeholder engagement. Harding cannot claim ignorance; the concealment emerged publicly on her watch. She cannot claim inability to act; she chairs the organisation. She cannot claim investigation inappropriate; transparency demands accountability.

The question is whether she possesses courage to investigate failures even when they implicate the institution she leads and colleagues she serves alongside. Does transparency mean releasing uncomfortable documentation or offering reassuring rhetoric whilst maintaining opacity? Seven years of concealment violated chartered duties, statutory obligations, and basic stakeholder engagement principles. Roger Weatherby, Paul Fisher, Sandy Dudgeon, Scott Bowers bear responsibility. But accountability now centres on Harding because she made transparency her standard.

She can provide full accounting, release documentation, implement binding reforms, and prove transparency commitments genuine. Or she can maintain silence, protect the institution, and confirm proclaimed values were rhetorical cover for continued opacity. The racing community—and stakeholders whose interests Section 172 requires her to serve—is waiting. Her procrastination is becoming its own answer. The question is whether she's brave enough to prove that answer wrong.

If she isn't, British racing will have its definitive evidence that The Jockey Club's self-governance model has failed beyond redemption and that meaningful reform can only come through external imposition. The choice, for now, remains hers. But patience is not infinite, and silence has its own eloquence.