2025 Budget Latest : Racing's Reprieve: Inside the Budget Deal That Saved British Horseracing

How an unlikely alliance of Treasury pragmatism, industry lobbying, and newspaper campaigns delivered racing from the brink—and what the numbers reveal about the sport's narrow escape. Plus: why bookmakers may exact revenge through the media rights backdoor.

HORSE RACINGPOLITICSGAMBLINGSPORT

Ed Grimshaw

11/24/20259 min read

When Rachel Reeves rises in the Commons on tomorrow to deliver her budget, British horseracing will discover whether it has secured the most improbable political victory of the year, or merely postponed an inevitable reckoning. The evidence, pieced together from Treasury sources, operator analysis, and the Financial Times's authoritative reporting, suggests the former—but the margin for complacency is precisely zero.

The base case, carrying a 55-65% probability, represents what one might call "manageable pain." The Chancellor will announce what the FT terms a "two-tier system": online sports betting duty rising modestly from 15% to 17-18%, Machine Games Duty nudging up from 20% to 21-22%, whilst horserace betting—the lifeblood of the sport—remains explicitly exempted at 15%. Land-based betting shops dodge the bullet entirely on General Betting Duty.

This outcome would cost racing £8-14 million against a £108 million baseline levy. Uncomfortable, certainly. A 5-8% prize money reduction necessitates difficult conversations. But existential? Hardly. Between 50-100 betting shops close rather than 3,400. Employment losses number hundreds rather than tens of thousands. The sport survives essentially intact.

One might even call it a win. Until, that is, one considers the scorpion crossing the river on the turtle's back, and recalls that nature—particularly the nature of gambling operators facing margin compression—has a way of reasserting itself.

The Numbers That Tell the Real Story

Yet these topline figures obscure a more fascinating narrative: how racing navigated between catastrophe and salvation, and why the probability distribution clustering around this moderate outcome tells us as much about modern Treasury thinking as it does about gambling policy.

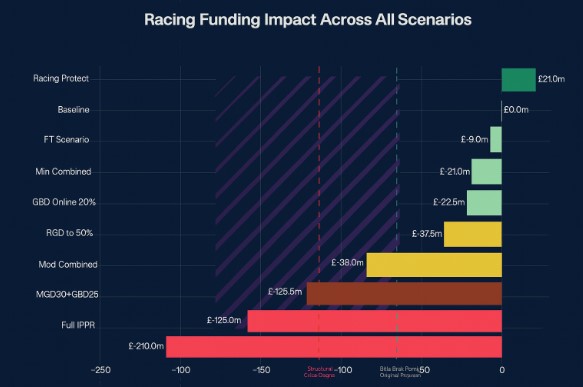

Consider the alternative scenarios that haunted racing executives through the autumn. The IPPR proposal—Remote Gaming Duty at 50%, GBD harmonised at 21%—would have extracted £146-260 million from racing's funding base. Not a budget cut. A decapitation. The modelling is unambiguous: 10+ racecourse closures, wholesale trainer bankruptcy, 1,800+ betting shops shuttered, and the very real prospect of government intervention bordering on nationalisation.

Even the intermediate scenarios—Scenarios 5-7 in the comprehensive analysis—presented structural challenges that would have reshaped racing fundamentally. Funding swings of minus £116 million to plus £27 million (the latter representing illusory gains from competitors' market exits) translate to 15-25% prize money reductions, significant trainer attrition, and racecourse consolidation. This is the territory where industries don't merely contract; they transform.

What prevented this? The answer illuminates how evidence-based advocacy can still penetrate Treasury orthodoxy, provided the evidence is sufficiently robust and the political incentives sufficiently aligned.

The Anatomy of a Lobbying Success

Racing's "Axe the Racing Tax" campaign achieved something remarkable: it made the Treasury confront second-order effects. The Betting and Gaming Council's operational analysis, whatever one thinks of industry special pleading, provided granular data on cascade mechanisms that Whitehall couldn't dismiss. Each percentage point of Machine Games Duty increase compresses betting shop margins by roughly £1-2 million industry-wide. Below a 2-3% pre-tax margin threshold, shops become uneconomic. Closures don't just eliminate direct employment; they trigger a multiplier effect of 1:3 to 1:5 into racing's employment base.

This isn't the stuff of press releases. It's the grinding arithmetic that determines whether Fakenham survives, whether northern trainers can sustain yards of twenty horses, whether racecourse catering staff have jobs next summer.

The Treasury, to its credit, appears to have listened. The FT's reporting on 16 November—citing "Treasury sources" with the specificity that suggests genuine inside access—described racing securing a "reprieve" from the original harmonisation proposal. City AM's subsequent reporting that Reeves aims to raise "around £2 billion" (across all tax measures, not just gambling) reinforced the moderate scenario. Gambling taxes representing 3-5% of the Chancellor's total tax strategy suggests revenue optimisation, not scorched-earth extraction.

Racing celebrated. Bookmakers, one imagines, smiled thinly and reached for the spreadsheets.

What the Cascade Mechanism Reveals

The Machine Games Duty decision merits particular scrutiny because it exposes the trade-offs facing any Chancellor attempting to squeeze revenue from vice without destroying the tax base.

At 21-22%—the most likely outcome—operators absorb margin compression through efficiency drives and selective closures. Fifty to one hundred shops disappear from lower-margin locations. High streets notice, but the network survives. Racing funding drops by that £8-14 million, absorbed through prize money adjustments and cost controls.

At 25%—Betfred's stated breaking point—we enter Scenario 7 territory: 382 shops closed by a single operator, 1,400-1,800 across the industry, racing funding down £146-180 million. This is structural damage requiring years to repair.

At 50%—the IPPR proposal that Gordon Brown championed—we're discussing functional market collapse. The 59% betting shop closure rate doesn't just eliminate high-street presence; it destroys the informal information network that connects betting culture to racing attendance, racecourse revenues to sponsor interest, and ultimately determines whether the sport remains economically viable outside elite metropolitan fixtures.

The Treasury's apparent choice of 21-22% suggests it has internalised these dynamics. It needs revenue without triggering cascade collapse. It wants to tax gambling's "fair share"—Reeves's preferred formulation—without inadvertently subsidising black market operators who pay no levy to racing whatsoever.

The Black Market Variable

This consideration may prove decisive. Current estimates place black market gambling at 5-7% of the total market. The FT Two-Tier Model would push this to 6-9%—a manageable degradation costing perhaps £10-20 million in revenue migrating offshore. Aggressive scenarios would drive 6-8 percentage points of additional market share to unlicensed operators, representing £60-100 million in lost Treasury revenue and devastating racing's levy base.

Industry warnings about black market migration often read as self-serving scaremongering. But the arithmetic is straightforward: if regulated operators' effective tax rate approaches 50% whilst black market operators pay zero, customers defect. Not en masse—most prefer regulated safety and convenience—but enough to matter. Particularly the high-volume customers whose betting generates disproportionate levy contributions.

The Chancellor faces an optimisation problem, not a moral crusade. Extract maximum sustainable revenue without triggering market structure changes that reduce total yield. The moderate scenario threading this needle suggests Treasury modelling has become more sophisticated than critics acknowledge.

The Revenge of the Bookmakers: Death by a Thousand Renegotiations

Here, however, we encounter the delicious irony that racing's political victory may prove pyrrhic in ways the British Horseracing Authority hasn't yet contemplated.

To understand the magnitude of what's at stake, one must appreciate the full scope of bookmaker contributions to British racing. The statutory levy of £108 million represents merely the visible portion. Add media rights payments (approximately £80-100 million annually for racing content across terrestrial, satellite, and digital platforms), plus direct sponsorship of races, courses, and festivals (£140-150 million annually), and the total reaches approximately £350 million. Bookmakers, in other words, fund roughly 70-75% of British racing's entire economic ecosystem.

This isn't a customer relationship. It's a dependency so profound that "symbiotic" understates the dynamic. Racing doesn't have bookmakers as partners; it has bookmakers as life support.

Bookmakers, having absorbed 1.5-2.5 percentage points of margin compression to protect racing's exemption, now face their own optimisation problem. One cannot squeeze profits from operations without compensating elsewhere. The obvious targets? Media rights payments and sponsorship deals—the very mechanisms racing hoped would offset levy reductions.

When these contracts come up for renewal—and they will, with major deals cycling through 2026-2028—racing will discover that bookmakers possess excellent memories and impressive actuarial capabilities.

Consider the negotiating dynamics. Flutter Entertainment, having just absorbed MGD increases that compress group margins, sits across the table from Arena Racing Company discussing media rights renewal. The conversation might proceed thusly:

"We notice you successfully lobbied for a racing exemption that cost us £12 million in additional tax burden. Congratulations. Genuinely. Impressive advocacy. Now, about this media rights fee—we were paying £25 million annually across our brands. Our revised valuation suggests £17 million represents fair market value. Given, you understand, our updated cost structure."

Racing protests: "But the content drives betting volume!"

"Indeed. At margins now compressed by your exemption. We've recalculated the customer lifetime value of racing punters versus football punters. The differential narrowed considerably once we factored in the tax asymmetry. Take the £17 million or we'll redirect marketing spend toward markets with better unit economics. Perhaps Turkish basketball. Lovely margins on Turkish basketball."

The Arithmetic of Retaliation

Estimating the potential hit requires examining contract cycles and margin pressure transmission mechanisms.

Media rights compression (2026-2028 renewals): Operators could justify 25-35% reductions in rights payments, citing margin compression and alternative content availability. On an £80-100 million base, this represents £20-35 million annual reduction. Even a conservative 20% haircut delivers £16-20 million in "savings" that operators can redirect toward products with healthier margins.

Sponsorship recalibration: Major race sponsorships currently total £140-150 million annually across all operators. Operators facing margin pressure will scrutinise ROI more aggressively. Expect 15-25% reductions as deals renew, representing £21-37.5 million annually. The Grand National might retain its lustre, but the Betfred Gold Cup at Cheltenham? Perhaps the "Efficiency Drive Silver Plate" has a certain ring to it.

Course partnerships and fixture support: Smaller deals for individual meetings or season-long course partnerships might decline 20-30% as operators optimise marketing spend toward higher-margin products. Racing has approximately £30-40 million in such arrangements. Estimate £6-12 million annual reduction.

Combined potential impact: £47-84.5 million annually by 2028, with a central estimate of approximately £60-65 million.

This, one notes with grim amusement, represents roughly 5-6 times the £8-14 million racing "saved" through its budget exemption. The money doesn't vanish; it simply migrates from one ledger to another, whilst racing's leadership congratulates itself on political acumen.

Bookmakers won't announce this openly. They'll cite "market conditions," "evolving customer preferences," and "portfolio optimisation." Racing Post will run earnest features about "diversifying revenue streams" and "reducing dependency on gambling." But the CFOs will know. Racing will know. And the Treasury, having squeezed bookmakers to protect racing, will watch with detached interest as market forces restore equilibrium through alternative channels.

The exquisite irony? Racing's £8-14 million levy "saving" could trigger £60-65 million in commercial revenue reductions—a multiplier effect of approximately 5:1. One struggles to recall a lobbying victory with quite such spectacular own-goal potential.

Political Economy and Racing's Unlikely Champions

Yet economic logic alone doesn't explain racing's apparent salvation. Political economy matters. The Sun's campaign protecting betting shops provided cover for restraint. Victoria Starmer's reported enthusiasm for racing may have mattered at the margins—though scepticism about spousal influence on fiscal policy remains warranted. More significant was the awkward truth that aggressive gambling taxes hit working-class communities hardest, complicating Labour's narrative about "fair" taxation.

Racing also benefited from fortunate timing. Had this budget occurred during a moral panic about gambling harm—a Jamie Forrest documentary, a high-profile suicide linked to betting losses—the political dynamics would have shifted decisively toward restriction. Instead, it arrives at a moment of relative public quiescence on the issue, allowing Treasury technocrats to prioritise revenue optimisation over symbolic gestures.

What Wednesday Reveals

The Chancellor's precise language will determine whether this analysis proves prophetic or embarrassingly premature. Listen for "two-tier system" and "racing protected"—confirmation of the base case. "Harmonisation" or "integrated duty structure" signals escalation toward more aggressive scenarios. The specific Machine Games Duty figure matters enormously: 21% represents relief, 25% represents serious concern, 30% represents crisis.

The 15% probability assigned to catastrophic outcomes remains non-trivial. Reeves could conclude that revenue maximisation overrides sector protection. Recession could force emergency measures. Anti-gambling advocacy could resurface with devastating timing. These are tail risks, but tails exist for a reason.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Racing has apparently secured manageable damage rather than existential threat. But "manageable" still means hundreds of job losses, prize money cuts, and structural pressures on marginal courses and smaller trainers. It means recognising that racing's economic model depends on gambling taxation remaining moderate, operator margins staying viable, and the regulatory framework not collapsing into prohibition-by-taxation.

It also means acknowledging that winning political battles sometimes merely relocates commercial warfare to different terrain. When Sky Bet's finance director sits down to review the racing media rights budget in 2027, he won't be thinking about the sport's cultural heritage. He'll be thinking about margin compression, shareholder returns, and how to explain why his company subsidises an industry that lobbied successfully to increase his tax burden.

The sponsorship boards at Cheltenham 2028 may look rather different. Fewer betting brands, perhaps. More oligarch-adjacent "consulting firms" and Middle Eastern sovereign wealth vehicles seeking sportswashing opportunities. One imagines the BHA will dress this up as "diversification."

This is hardly a position of strength from which to lecture others about moral hazard.

The Longer Game

When Reeves sits down on tomorrow afternoon, British horseracing will know its immediate future. The odds favour survival—85% confidence in outcomes compatible with continued viability. But the sport has learned, or should have learned, that its existence depends on political choices that could reverse at any budget, any economic crisis, any shift in public sentiment.

More pertinently, it has demonstrated to its primary commercial partners—bookmakers who provide approximately £350 million annually or 70-75% of racing's total funding when levy, media rights, and sponsorship are combined—that racing will lobby for preferential treatment that exacerbates operators' margin pressure. This creates fascinating game theory for future negotiations.

Bookmakers cannot legally reduce levy contributions; those are statutory. But media rights and sponsorship operate in genuine markets where pricing reflects both content value and relationship quality. Racing has just reminded operators that when political interests diverge, racing chooses racing. Operators, being rational economic actors operating in competitive markets, will respond with cold-eyed cost-benefit analysis rather than sentimental attachment to the "Sport of Kings."

The £60-65 million potential reduction in commercial revenues by 2028 may not materialise in full. Perhaps operators conclude that maintaining racing exposure serves broader strategic interests. Perhaps alternative revenue sources emerge. Perhaps racing's negotiators prove sufficiently skilled to minimise damage.

But racing has burned goodwill it didn't know it possessed, with creditors it couldn't afford to antagonise. The invoice arrives later, denominated in basis points on media rights renewals and mysteriously reduced sponsorship budgets. By 2028, the BHA may discover that winning in 2025 merely determined the battlefield for losing in 2027.

The mathematics are rather elegant, in a dark sort of way: save £12 million in levy today, lose £60 million in commercial revenue tomorrow. It's the sort of trade-off that looks brilliant in the press release and catastrophic in the three-year budget forecast.

That's not salvation. That's precarity with better odds than yesterday, and a commercial relationship now conducting negotiations through slightly gritted teeth whilst recalculating the net present value of continued partnership.

One expects the champagne in Holborn will taste excellent on Wednesday evening. One wonders about the vintage they'll be serving in 2028. If current form holds, it'll be whatever's on special offer at Tesco. Expect some grovelling in the next 2 years.